The OSA has available resources and information to assist teachers, naturalists, museum and community educators, and archaeologists with teaching archaeology to public audiences. If you are planning or considering the development of lessons, activities, and curricula focused on archaeology or have any additional questions, we encourage you to reach out to us! There are many misconceptions about both archaeology and Indigenous cultures that perpetuate due to improper research, incorrect or outdated information online, or lack of access to appropriate resources. If we do not have the resource or

Resources

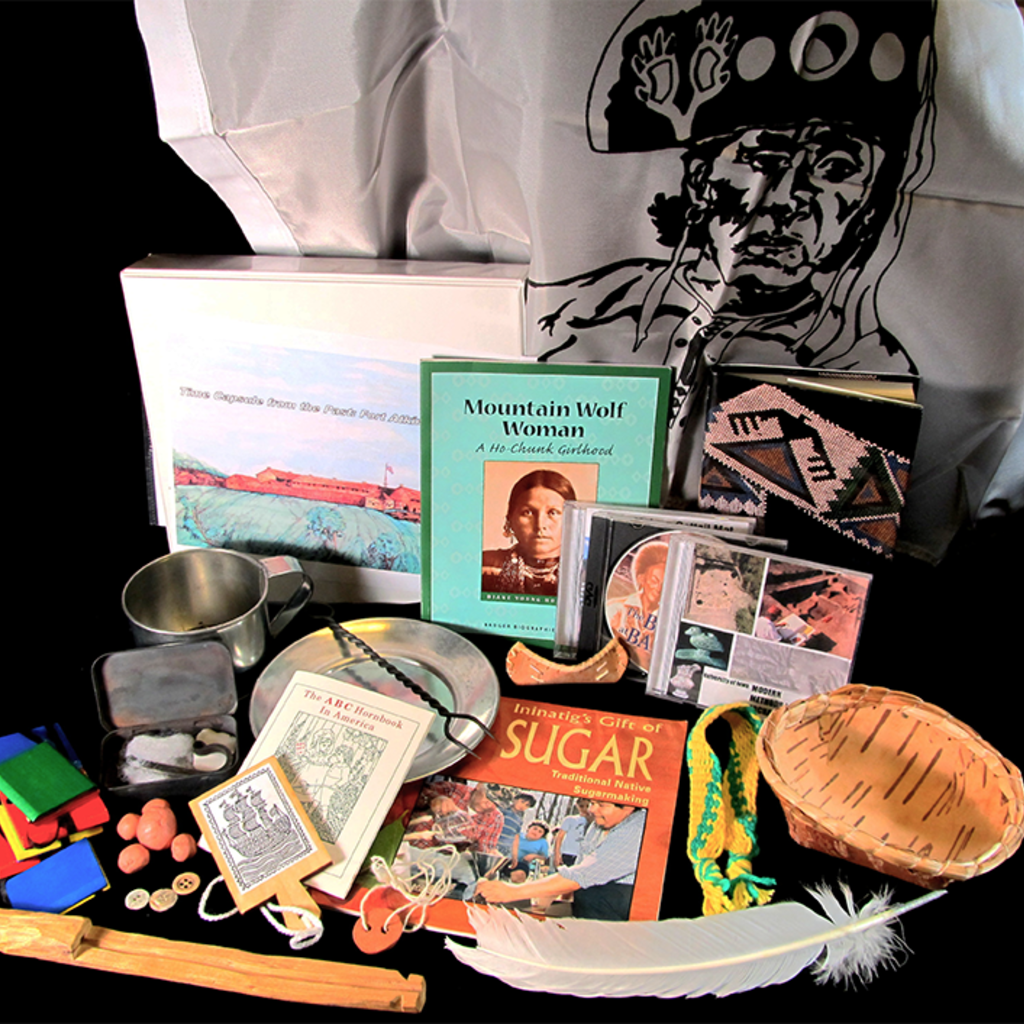

Archaeology Discovery Trunks

OSA rents comprehensive teaching resource kits to Iowa educators. Check out our eight different themes that cover Iowa's archaeological past from 13,000 years ago through 1800s dairy farming.

online resources

Many of the digital resources found on our Research, Explore, Visit page are adaptable for use in classrooms and lessons.

Lessons

Videos

Iowa Archaeology on YouTube

Find newly produced educational videos, livestreamed lectures and interviews, digitized materials from the OSA archives, man with a place-based, Iowa focus. We also maintain playlists on Archaeology in the Classroom and Iowa Indigenous Culture.

Common Terminology

Archaeology or Archeology?

Both archaeology (using the diphthong "ae") and archeology (without the second "a") are accurate spellings of the word in the English language. The variant "e" spelling became widely used by printing presses in the late 19th century, resulting from a decision by the U.S. Government Printing Office to economize printing. The National Park Service and various state governments adopted this version.

OSA uses the traditional diphthong when spelling archaeology and its derivatives. The formal name for the Iowa Archeological Society, however, does not use the diphthong.

Negative Connotations of the term "Prehistoric"

Archaeologists who study the ancient Native American past are moving away from using the term prehistoric. Many of OSA's Tribal partners and Indigenous communities across North America feel that this term expresses "before history" and implies that anything before the arrival of Europeans is not "history". For this reason, OSA is shifting to the terms "precontact" and "ancestral Native American," with the latter reinforcing the connectedness of these ancient people with modern Native Americans. One exception in Iowa is the archaeological time period designation, "Late Prehistoric," which has been used as an official term for decades and is embedded in the literature.

Time Period and Archaeological Culture Designations

The following terms are not terms created or used by Native Americans descendant to Iowa to refer to their ancestors. They should be applied to a time period or archaeological culture and not as names for a group of people. OSA has not always done this in the past, but revisions and newly created content will not refer to people as time periods, e.g. "the Paleoindian people" or "Oneota people." Alternatives could include, "People during the Paleoindian time period" or "The Oneota cultural tradition."

The term “Late Prehistoric” refers to a time period designation created by archaeologists to help define the chronology of Iowa’s archaeological past. This archaeological time period begins approximately A.D. 900-1000 and ends with the arrival of Europeans. The Late Prehistoric time period is characterized by significant Indigenous technological innovations and adaptations such as large-scale agriculture focused on corn, year-round villages and settlements, use of the bow and arrow, and increased social and economic complexity.

Mill Creek, Glenwood, Oneota, and Great Oasis are archaeological terms for cultural designations based on material evidence for regional/geographical, temporal, and technological patterns. Regionally, Mill Creek sites are found in northwest Iowa, Glenwood sites in far southwest Iowa, Great Oasis sites mostly in central to northwest Iowa, and Oneota sites across the state and beyond. We have learned from archaeological research and through Indigenous oral histories shared with us that the people in the cultural tradition that archaeologists refer to as Oneota are direct ancestors of today’s Iowa (Ioway), Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), Oto, Missouria, Ponca, and Omaha tribes while the Mill Creek archaeological culture is ancestral to today’s Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Arikara, and Hidatsa), among others. The Glenwood archaeological culture is likely ancestral to many Tribes historically known from the Plains.

Important Notes

Indigenous cultures are not frozen in the past

Native Americans live all over Iowa and the Midwest and have a unique and thriving culture. They honor many traditions from the past, but have also adapted to living in a contemporary society, just like Europeans settlers did. The most important message our Indigenous partners want people to know is, “WE ARE STILL HERE.” Avoid continually using the past tense to talk about Native Americans. We strongly encourage you to talk about contemporary Indigenous communities in Iowa whenever you teach about ancestral Native Americans. Please let us know if you need additional resources!

Avoid an emphasis on digging

Be cautious of an emphasis on digging, particularly with teaching tools such as sand-box excavations or mock digs. While fun for children, many archaeologists would agree that sand box excavations require a lot of work for a very inauthentic experience with little value in learning site formation and stratigraphy. They also perpetuate a misconception that all archaeologists do is dig or that it’s the most important part of the job. Through assessment, evaluation, and rigorous study, archaeology educators are learning that when digging is involved, most other information about the archaeological process or past peoples is not retained by teachers or students! Talk about a major “a-ha” moment!

Be aware of stereotypes and cultural appropriation

When talking about Indigenous culture, avoid these common stereotypes, phrases,

and concepts:

- “Close to nature” or “they never wasted anything”: It is better to teach about how Ancestral Native Americans had an intimate understanding of the resources in their environment and were careful and creative in their use of available resources.

- “Primitive”: This word implies something that doesn’t require extensive skills or knowledge, aka “backwards.”

- “They felt” or “Indians believed”: Avoid phrases that freeze people in the past and/or generalize an entire group of people. Besides generalizing them as a monolithic group, it makes too many assumptions about the structure of religious and spiritual practices of Native Americans. Also, referring to how someone felt or what a group believed presumes that you are speaking from a place of authority and represent that group, when you likely do not. If you are referring to specific evidence or an ethnography, quote the source.

- “Spirit Animal”: Learn more here

- Headdresses: a sacred item, highly specific only to certain tribes

- Creation stories or just-so stories: Sharing such stories is encouraged, but please make sure they are stories that are written by Native Americans and shared with the public; for example, the Keepers of the Earth environmental education series or books on ecology by Gregory Cajete. Always check your sources! Many creation stories are not meant for sharing.

A special note on tipis

We notice educators across Iowa erect, discuss, and center lessons on Native American heritage around tipis. The tipi shelter is highly specific only to certain tribes. This shelter may be regionally appropriate for far north or northwest Iowa, but not for most of the state! In the great plains of far western Iowa, various types of earth lodge shelters housed the ancestors of Native Americans. In the woodlands of eastern Iowa, round wooden frames covered with cattail, reed, or grass mats were common for winter camps, while summer villages contained long houses. The Meskwaki call these smaller shelters wickiups. The Ho-Chunk, who are one of the descendant tribes related to those who archaeologists place in the Oneota cultural tradition, know them as a ciporoke (“chee-poe-doe-kay”).

A special note on atlatls

When teaching about archaeology or Native American culture, many educators and archaeologists sometimes place a heavy focus on throwing spears with a tool known as an atlatl.

This is a great activity that gets a lot of students really excited! Spear-throwing can very easily turn into a time-filler or “activity mania,” aka an activity with little to no educational context. If you’re doing spear throwing with your students, emphasize these important points:

- This is an ancient technology, much older than the bow and arrow!

- Atlatls were used all over the world, including in Iowa, for tens of thousands of years. In Iowa, bow and arrow technology was first introduced about 1800 years ago. That means that people hunted with spears in Iowa for over 11,000 years before learning to use the bow and arrow! Even then, people continued to hunt with spears. Eventually, the bow and arrow became the preferred hunting tool.

- It wasn’t just used for large prey like mammoths and bison. Skilled hunters could take down animals of all sizes with an accurate throw of the spear.

- Women can hunt just as well as men! In fact, using an atlatl does not require “draw force” like with a bow, you can use it with one hand.

- It’s physics!! An atlatl is a lever that enables wrist rotation to make a substantial increase in the velocity of a thrown spear. By using an atlatl, you can throw a spear further and it will hit its mark harder. This force could penetrate the 6-inch skin of a mammoth! Conduct student experiments with and without an atlatl to throw the spear. What are their observations?

- “Atlatl” is an Aztec word. We do not know what people Indigenous to Iowa called this tool.

- We tend to stand in one spot and throw at a stationary target, placed about 15 meters or 50 ft away. Ancient hunters and their prey were both on the move! It is estimated that a typical hunting and target range is typically 10 to 30 yards, but the world-record throw is over 848 feet.

- There are many other hunting techniques that are often overlooked, such as snares, bolos, and nets.