Humans have lived in what is now the state of Iowa for at least 13,000 years. Iowa’s agricultural heritage has its roots in the ancient past—people were growing corn in Iowa hundreds of years before Euroamerican settlement. The diverse Indigenous cultures inhabiting the region and the early Euroamerican pioneers made many contributions to our modern world.

Not only have people lived here for thousands of years, but they have been buried here as well. The earliest burials included isolated graves and large ossuaries, or mass graves. Approximately 2500 years ago during the Woodland time period, people began to build conical-shaped mounds to inter their dead. This practice continued for almost 1500 years. Later precontact and early historic American Indian burials included isolated graves and cemeteries. With Euroamerican settlement, additional graves and cemeteries dotted the landscape.

Unfortunately many ancient and historic burials have been destroyed through construction, farming, erosion, and vandalism. Because the vast majority of Iowa lands are privately owned, we rely a great deal on the stewardship of Iowans to protect known burial sites, which include ancient and historic cemeteries and constructed mounds and other earthworks. On state-owned lands, we rely on the stewardship of Department of Natural Resources staff.

Through stewardship efforts by landowners and land managers, the remaining remnants of these past inhabitants of Iowa can be conserved.

Vegetation Management for Burial Sites

One approach to conserving mounds or other unmarked burial sites is to manage or modify existing vegetation to encourage soil stabilization and discourage erosion. The following are practices for vegetation management on mounds and other burial sites that meet the approval of OSA and the OSA Indian Advisory Council.

- No heavy machinery needed for vegetation management (e.g. tree removal or seeding) should be placed on or driven over mounds or other burial sites. Consult with the OSA Bioarchaeology Program to determine appropriate buffer zones.

- At maximum, small riding lawnmowers can be used to mow grass covering mounds. Mower decks should be set to the highest level possible and mowing should only occur when conditions are dry to prevent rutting.

- Large trees should be removed from mounds because they can cause unwanted damage if uprooted. However, consult with the OSA and appropriate tribes before doing so as certain trees can be of cultural significance. They should be cut flush with the ground surface, and the stump left in place. Tree removal is ideally done in the winter when the ground is frozen or when soil conditions are dry enough to avoid unwanted rutting by necessary vehicles/machinery.

- Controlled burning of a site and re-seeding with native species is the preferred method for modifying existing vegetation (herbicides should be avoided to eliminate invasive species if possible). Assistance from the local County Conservation Board staff or the County Roadside Vegetation Manager should be sought.

- If burning is not possible, remove unwanted weeds and undergrowth with hand tools only if necessary. Do not dig or pull out roots. Maximum coverage of mounds by low growth vegetation (with the exception of large tree species), especially in areas that are infrequently visited by the public, is ideal for both their stabilization and protection.

- If disking and seed drilling is required for seeding the area surrounding a mound or burial site appropriate buffers must be maintained. No disking nor seed drilling should be done on or immediately adjacent to mounds or other burial sites.

- Preferred seeding methods of such sites are broadcast/hand seeding or hydroseeding.

- Seeds used should be primarily local ecotypes that would match historical vegetation of the area.

Locating Unmarked Cemetery Burials

Burials are often poorly marked in cemeteries, and many cemeteries suffer from poor or nonexistent record keeping. Cemetery plots are typically treated as property, and conflicting claims on a plot can lead to legal headaches for everyone concerned. Likewise, the disturbance of an unmarked grave by a subsequent burial can be traumatic for all the families involved. For these reasons, it is important for the caretakers of a cemetery to do their best to verify that a plot is empty before someone is buried in it or before the plot is sold or traded.

This information is relevant only for the identification of graves which can reasonably be considered less than 150 years old. Older graves, including Native American and pioneer graves, fall under the jurisdiction of the OSA. If you are dealing with a grave site you suspect is more than 150 years old, contact the OSA Bioarchaeology Program. You must also contact us if ancient human remains are inadvertently discovered during any ground disturbing activity (per Iowa Code sections 523I.316.6 and 685-11.1); all activity must cease, the remains must be protected, and local law enforcement and the OSA must be notified as soon as possible.

This guide is intended to help cemetery caretakers and the general public understand the options that exist for locating unmarked graves in Iowa. The most common ways of locating graves are discussed, as well as their advantages and disadvantages. It should be noted that no process is foolproof in finding unmarked graves. There are specific laws related to disturbance of graves in Iowa. If you are unsure if you are allowed to conduct an investigation, reach out to a contact for burial issues.

As cemetery caretakers well know, what you see on the surface does not always reflect what is below. Grave markers can be at the head, foot, or center of a grave, or can be some distance from the grave. Burials can be oriented in any direction relative to a marker or nearby burials. The markings on the gravestone may face towards or away from the burial. Multiple individuals may be buried under one marker. Many burials lack markers, typically because the original marker was made of wood or because of vandalism. Markers may be situated over empty graves. Well-maintained cemeteries typically do not have depressions over a grave; if there is a depression, it may be far larger or smaller than one would think necessary. Depressions are not always signifiers of graves, since grave diggers can borrow soil from nearby areas to fill in low spots, creating depressions that resemble graves, or intentionally mound significant amounts of soil on top of graves.

In sum, you cannot assume that surface indications have anything to do with what is below the surface. If records are inadequate, some sort of remote sensing or subsurface testing is needed to locate burials. Described here are the most common techniques.

Rod Probing

Probably the most common way to search for graves is to probe the soil in the area with a 6-footlong rod with a blunt end and a T-shaped handle. These rods can be purchased commercially or be made by the user. The soil is probed in various spots looking for the resistance one would expect from a coffin or vault.

Advantages: Inexpensive, easy to use, generally accurate for recent burials in coffins or vaults.

Disadvantages: Invasive, so families may object. Cannot find burials that were not in coffins. Cannot find wooden coffins that have rotted, which is very common among graves from the 1800s and early 1900s. The coffin and remains decay and the coffin void fills in, leaving no resistance or voids to be found by the probe. Very difficult to find small coffins of infants or children. Rocks in the soil often give false readings, and it is very difficult to probe when the ground is hard or frozen.

Soil Coring

A more-exact method of probing is soil coring, in which a 3/4-inch or 1-inch diameter hollow tube is inserted into the ground above a suspected grave. The core is pulled out, and the soil examined for evidence of disturbance through comparisons with nearby undisturbed areas. This work should be done by a trained archaeologist or soil scientist, since the differences between a disturbed and undisturbed soil can be very subtle, especially if the soil is homogenous or very complex.

Advantages: better than rod probing, since it can detect burials even if the coffin is severely decayed. Cost is usually less than remote sensing. There are numerous qualified archaeologists in Iowa who can help; Iowa archaeology firms are listed at the end of this document.

Disadvantages: Invasive, so families may object. Requires an archaeologist or soils scientist, so cost is greater than rod probing. Difficult or impossible in rocky soil. Often, soil difference can be so subtle that even a trained archaeologist cannot tell if a grave exists for certain or not, especially if the original soil matrix is very homogenous or if the upper soil layers are disturbed by non-grave activity such as earth moving or burrowing animals. It is very difficult to core when the ground is hard or frozen.

Formal Excavation

The most-definitive way of determining if a burial exists in a plot is formal excavation. Formal excavation is different than grave digging; typically, a grave digger will not notice if they are digging an occupied grave until it is too late and the coffin or burial is damaged or destroyed. Human remains are occasionally found in back dirt or borrow piles at cemeteries, since the grave digger cannot always tell if they have gone through an existing grave. Formal excavation is different than exhumation, in which a fairly-recent burial from a known grave is removed; many funeral parlors or medical examiners can arrange for exhumation. In contrast, formal excavation is the systematic removal of soil in a controlled fashion to locate suspected graves while causing minimal damage to them. Formal excavation is best performed by a trained archaeologist who has an understanding of soils and excavation methods. While there are many ways to perform formal excavation, a common way is to use a wide, toothless backhoe to slowly strip away the soil in level layers a few inches at a time. This allows the archaeologist to check for evidence in the soil of a grave shaft (the filled-in grave hole) above the burial. Once evidence of a burial is encountered, archaeologists can map the burial and leave it in place. If a disinterment permit has been obtained from the Department of Public Health (and the State Archaeologist if the interment is over 150 years old), an archaeologist can carefully excavate the remains for reburial elsewhere, after a consultation with the person who obtained the permit. If the remains and effects are removed, they can be studied to help determine the identity of the individual. Formal excavation can also stop well above the grave if there is evidence of a shaft.

Advantages: Almost fool-proof and, if properly done, will provide a definitive answer. Can be performed in any soil type, rocks are not a problem. Excavation can provide information about not just if a burial is located there but can also provide information needed to determine the identity of the buried person. There are numerous qualified archaeologists in Iowa who can help; Iowa archaeologists are listed at the end of this document.

Disadvantages: Highly invasive, so families may object. Expensive; it requires an archaeologist and machinery, and possibly laboratory time. There is always a chance that a very ephemeral burial will be missed and destroyed by machinery, although this is unlikely.

Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR)

With GPR, a radio or microwave signal is sent into the ground and the reflected signal is recorded. The time it takes for the signal to return reflects the depth of penetration, and the returning signal can be stronger or weaker depending on the type of material it is passing through and reflecting off. This data can be used to make an image of the subsurface. A GPR technician will walk an antenna over an area, recording data. This data is processed in a computer to create a two- or three- dimensional image of the subsurface. Under ideal conditions, the grave shaft and possibly the coffin or vault will be visible, but under normal conditions, only the upper part of the grave shaft is visible.

Advantages: GPR is non-invasive, so families typically do not object. Under ideal conditions, it can provide a highly-detailed image of the subsurface. GPR can often see-through surface disturbances. GPR is probably the best form of remote sensing if the clay content of the soil is low. Services are available in Iowa, for a fee, from the OSA. Other regional practitioners can be found listed below, or by contacting a firm listed with the Association of Iowa Archaeologists.

Disadvantages: GPR’s effectiveness depends on soil conditions; it does not work well in clay-rich, rocky, or saturated soils. GPR can be expensive and may not provide definitive results; some form of ground truthing may be necessary.

Resistivity

Resistivity can often be useful in finding graves, it is based on the principle that soils have differing moisture retention properties and therefore will conduct electricity differently. A small electric charge is run between spikes placed in the ground, and the resistance is measured. When a soil is disturbed, as in a burial, different types of soil are brought near the surface which have very slight differences in electrical resistivity. The surveyor will probe at close intervals over a large area collecting data, which is then downloaded into a computer to show areas of disturbed soils. In a cemetery, these often correspond to marked and unmarked graves.

Advantages: The spikes only penetrate a few inches into the soil, so it is relatively non-invasive and families typically do not object. Can give some idea if disturbances are deep or not. Under ideal circumstances, resistivity is quite effective.

Disadvantages: Resistivity is ineffective if the upper level of soil is disturbed over a large area (for example, by previous bulldozing), and it is ineffective under certain conditions, such as when the soil is very wet or very dry. Can be expensive. May be adversely affected by rocky soil.

Conductivity

Conductivity is often effective in finding graves. It works by applying a magnetic field to the ground surface. This magnetic pulse causes the soil to generate a secondary magnetic field, which is recorded to make a map. When a soil is disturbed, as in a burial, different types of soil are brought near the surface which have very slight differences in conductivity. The surveyor will walk an instrument over a large area collecting data, which is then downloaded into a computer to show areas of disturbed soils. In a cemetery, these often correspond to marked and unmarked graves.

Advantages: Conductivity is non-invasive, so families typically do not object. Can cover a large area in a fairly short period of time. It can be very effective under the proper conditions. Suitable instruments are often available from local soil scientists, but one must be certain the operator understands how to identify variation associated with graves.

Disadvantages: Conductivity is ineffective if the upper level of soil is disturbed over a large area. It is ineffective in the presence of ferrous metal (iron, steel, etc.), so the survey area has to be very clean and checked with metal detectors; metal markers, vases, etc., must be removed. It can be less effective if the soil is saturated, very dry, or rocky. It is affected by nearby power lines. Currently, there are no practitioners in Iowa; for regional practitioners, see the web page listed at the end of this document. Likewise, qualified archaeologists can also help you find a practitioner, a list of Iowa archaeologists is included at the end of this document.

Magnetometry

A sometimes effective way to quickly identify graves is with the use of magnetometers. Magnetometers are devices that measure minute changes in the magnetic properties of soil. When a soil is disturbed, as in a burial, different types of soil are brought near the surface which have very slight differences in magnetism. The surveyor will walk a magnetometer over a large area collecting data, which is then downloaded into a computer to produce maps that show areas of disturbed soils. In a cemetery, these often correspond to marked and unmarked graves.

Advantages: Magnetometry is non-invasive, so families typically do not object. Can cover a large area in a fairly short period of time. Can be very effective under the proper conditions.

Disadvantages: Magnetometry is ineffective if the upper level of soil is disturbed over a large area. Soils need to have significant iron oxide content, or it will not work. Ineffective in the presence of ferrous metal (iron, steel, etc.), so the survey area has to be very clean and checked with metal detectors; metal markers, fences, vases, etc., must be removed. Because of its limitations, magnetometry is often less effective than conductivity or resistance. Magnetometry can be expensive.

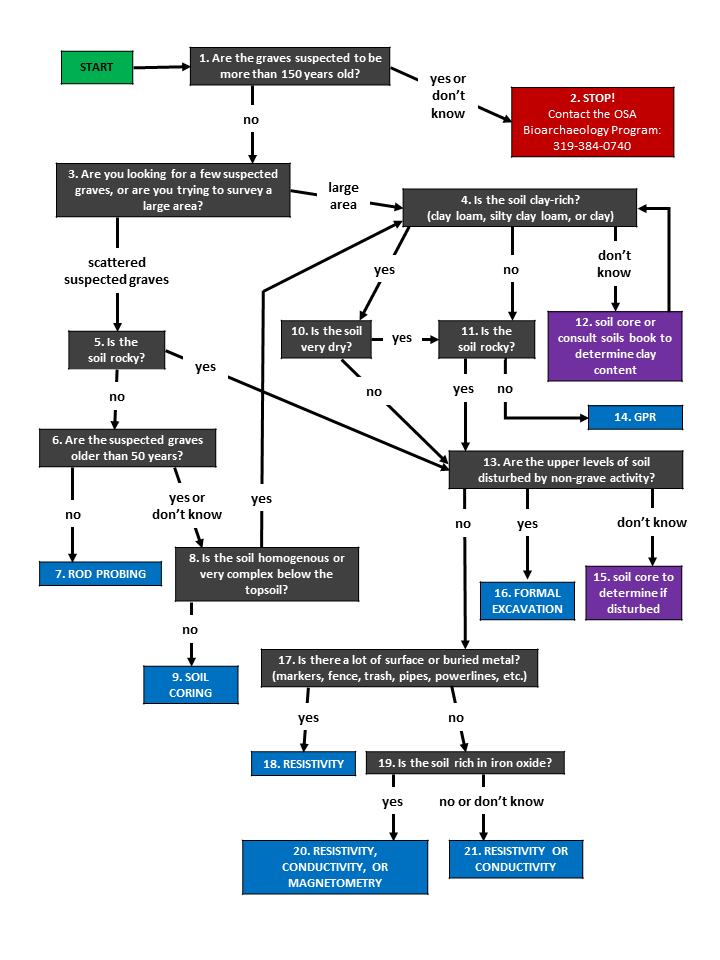

Decision Tree for Locating Unmarked Graves

Start of decision tree

- Are the graves suspected to be more than 150 years old?

- If YES or DON’T KNOW, go to Step 2.

- If NO, go to Step 3.

- STOP! Contact the OSA Bioarchaeology Program: 319-384-0740

- Are you looking for a few suspected graves, or are you trying to survey a large area?

- If LARGE AREA, go to Step 4.

- If SCATTERED SUSPECTED GRAVES, go to Step 5.

- Is the soil clay-rich? (clay loam, silty clay loam, or clay)

- If YES, go to Step 10.

- If NO, go to Step 11.

- If DON’T KNOW, go to Step 12.

- Is the soil rocky?

- If NO, go to Step 6.

- If YES, go to Step 13.

- Are the suspected graves older than 50 years?

- If NO, go to Step 7.

- If YES or DON’T KNOW, go to Step 9.

- Solution: ROB PROBING [end of decision tree]

- Is the soil homogenous or very complex below the topsoil?

- If NO, go to Step 9.

- If YES, go to Step 4.

- Solution: SOIL CORING [end of decision tree]

- Is the soil very dry?

- If YES, go to Step 11.

- If NO, go to Step 13.

- Is the soil rocky?

- If YES, go to Step 13.

- If NO, go to Step 14.

- Soil core or consult soils book to determine clay content and go back to Step 4.

- Are the upper levels of soil disturbed by non-grave activity?

- If NO, go to Step 17.

- If YES, go to Step 14.

- If DON’T KNOW, go to Step 15.

- Solution: GPR [end of decision tree]

- Soil core to determine if disturbed and go back to Step 13.

- Solution: FORMAL EXCAVATION [end of decision tree]

- Is there a lot of surface or buried metal? (markers, fence, trash, pipes, powerlines, etc.)

- If YES, go to Step 18.

- If NO, go to Step 19.

- Solution: RESISTIVITY [end of decision tree]

- Is the soil rich in iron oxide?

- If YES, go to Step 20.

- If NO, go to Step 21.

- Solution: RESISTIVITY, CONDUCTIVITY, OR MAGNETOMETRY [end of decision tree]

- Solution: RESISTIVITY or CONDUCTIVITY [end of decision tree]

Contact Information

Contacts for Burial Issues

| Name & e-mail | Phone |

|---|---|

| Lara Noldner: Office of the State Archaeologist Bioarchaeology Program (burials older than 150 years, can also answer general questions) | 319-384-0740 |

| Dennis Britson: Regulated Industries Unit, Iowa Securities Bureau (oversight of active cemeteries) | 515-281-5705 |

| Dennis Klein: State Medical Examiners Office | 515-725-1400 |

| Walker Hodges: State Medical Examiners Office | 515-745-0580 |

| Melissa Bird: Deputy State Registrar, Bureau of Vital Records at the Department of Public Health, Office of Vital Statistics | 515-281-6762 |

| Eric Dirth: Assistant Attorney General, Attorney General's Office | 515-281-8153 |

Remote Sensing Practitioners & Archaeologists

A list of regional practitioners of remote sensing (GPR, magnetometry, resistivity, conductivity) can be found at the North American Database of Archaeological Geophysicists. Since geophysics is an unregulated profession, ask for references and examples of final reports. Geophysicists affiliated with archaeological or engineering firms may be better choices, since archaeology and engineering are regulated professions.

Many archaeologists can subcontract a geophysicist on your behalf. A full list of qualified archaeologists working in Iowa, including out-of-state firms, is maintained by the Association of Iowa Archaeologists (AIA).

Iowa Archaeologists Who Conduct Geophysics

| Name & e-mail | Affiliation | Phone |

|---|---|---|

| Mark Anderson | Sanford Museum | 712-225-3922 |

| Colin Betts | Luther College | 563-387-1284 |

| Glenn Storey | University of Iowa Department of Anthropology |

319-335-1866 |

Farm and Rural Settings

Burial site maintenance and management should be designed to prevent damage to human remains and associated materials, and to preserve sites for the benefit of descendants and the public. The following management suggestions should result in minimal inconvenience to a landowner while still protecting burials.

Burial Sites over 150 Years in Age

If burial sites are located in an area currently used as a pasture, a change in land use may not be needed. Use of an area as a pasture causes minimal damage to burial sites, although erosion can be a potential threat. To reduce erosion and damage to burial sites, do not allow grazing during wet seasons. Also locate gates so livestock does not have to directly cross the burials.

If the area of the burial sites has never been cultivated, it should be left uncultivated. If it is currently being cultivated, erosion and additional damage to the burials can be minimized by leaving the surface of the burials in permanent grassy vegetation or by using no-till practices in the burial area.

Burial sites in timbered areas require minimal maintenance. Special consideration, however, needs to be given to the potential impacts from logging and tree falls. If an area is to be logged, visibly mark the burial area prior to the start of any logging activity to ensure that heavy equipment does not drive over the burial sites and to prevent fallen trees from being pulled over the burial surface.

Dead or dying trees on burial sites should be cut to prevent potential damage from uprooting during wind or ice storms. To do this, trees should be cut just above the ground surface and the stump chipped out by hand. The resulting cavity should then be filled with clean dirt (taken from a non-burial site location). Do not bulldoze, pull, or attempt to grub out the roots as this could cause extensive and unnecessary damage to the burials. As the root system naturally decomposes, additional dirt should be added to fill in any depression. Grassy vegetation should be encouraged. Heavy brush should be cleared from burial sites on a yearly basis. Cut off at or slightly above ground level, do not pull.

At no time should vehicles of any sort be driven onto or across burial sites. Fence posts, sign posts, utility poles, utility lines, etc., should not be placed in or on burial sites. Any tombstones that are present should be left intact.

Development Considerations

During construction, a buffer zone around the burial sites will help assure protection. In some cases, a 100-foot buffer zone has been recommended, and in other cases as little as a 25-foot buffer or less is suitable. The three concerns to be addressed in determining the size of buffer are:

- preventing disturbance during construction;

- protecting the site from erosion that could result from grading or other earthmoving activities related to construction;

- protecting the site from normal landscaping and everyday activities once construction is completed.

These concerns can be addressed by physically fencing off the mounds during construction to protect them from disturbance. The buffer and the fencing during construction provide protection from inadvertent damage by heavy machinery and help ensure that the site’s immediate surroundings are maintained in a relatively natural state and subjected to minimal erosion and other post-construction damage.

Following construction, any graded area should be stabilized to prevent erosion or undermining of the adjacent site. Normal landscaping and everyday activities should not disturb the burial site’s ground surface and not raise the possible perception of desecration. For example, using a burial site for tree or shrub plantings or as a garden plot would disturb the ground surface. Placement of a picnic table or playground equipment on top of a mound could be considered desecration, or at the very least, disrespectful. A mowed lawn, perennial flower garden (shallow plantings only), or prairie planting would all be low impact uses compatible with burial site conservation.

Long Term Preservation Options

Conservation easements and deed restrictions are among the options for long term preservation.

If you sell your property,

please alert the new owner of the presence of any burial sites and their legal responsibilities.